The Black experience at UMD pre-1968

Barred from the University

Before 1950, the University of Maryland was an all-white institution. University President Harry Byrd (tenure 1936-1953) and his successor, Wilson Elkins (tenure 1954-1970) pushed back against integration, arguing that Black students would be "happier" attending "their own" institutions, meaning Morgan State and Coppin State in Baltimore. In 1950, Parren J. Mitchell applied to UMD, hoping to obtain his Master's in Sociology. However, he was turned down due to his race. Represented by Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP, Mitchell successfully sued the University, forcing them to admit him to the graduate program, along with Esther McCready, who was admitted into the Nursing program in Baltimore. University administration attempted to offer Mitchell enrollment but not allow him to attend the main campus; however, Mitchell stood firm, attaining full student status.

In 1950, Parren J. Mitchell applied to UMD, hoping to obtain his Master's in Sociology. However, he was turned down due to his race. Represented by Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP, Mitchell successfully sued the University, forcing them to admit him to the graduate program, along with Esther McCready, who was admitted into the Nursing program in Baltimore. University administration attempted to offer Mitchell enrollment but not allow him to attend the main campus; however, Mitchell stood firm, attaining full student status.  Mitchell became the first Black person to graduate from the University of Maryland.The next year, in 1951, Hiram Whittle was admitted to UMD, enrolling in the College of Engineering. Whittle (pictured at right with his dorm-mates) became the first Black undergraduate to receive his degree at Maryland.

Mitchell became the first Black person to graduate from the University of Maryland.The next year, in 1951, Hiram Whittle was admitted to UMD, enrolling in the College of Engineering. Whittle (pictured at right with his dorm-mates) became the first Black undergraduate to receive his degree at Maryland.

After Brown v. Board of Education, the number of Black students enrolling grew to a steady trickle. Seven Black students enrolled at UMD in the fall of 1955, one year after Brown v. Board. Only one, Elaine Johnson Coates (left), graduated in 1959, becoming the first Black woman to graduate from UMD. The other six, including Coates' roommate, dropped out before the end of their first semester due to the unrelentingly hostile environment.

In a 2019 interview, Coates described her time at UMD as an incredibly lonely experience. She had no car, so she could not leave campus. For four years, no one would sit with her or talk to her. Practically the only time anyone talked to Coates was to shout racial slurs at her. She faced discrimination from professors, and white students would call her on her dorm phone to call her racial slurs. Coates persevered through four years of near-total isolation and hatred to become the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Maryland. A full oral history interview with Elaine J. Coates can be found here.

This was the environment for Black students at the University less than a decade before the BSU protest.

The Congress for Racial Equality and early activism

But this hostile environment does not mean that Black students and community members were not active in protesting racism. A delegation from the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) picketed the Maryland booth at the 1964 World's Fair, which took place in New York. This delegation included several UMD students. At the time, Maryland had no legal protections ensuring that Black citizens could not be barred from businesses in the state.

In June 1965, the Washington Suburban chapter of the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) picketed UMD in protest of Maryland's de facto segregation in higher education. Chapter president Michael Tabor sent a letter (visible at right – click to zoom) to then-President Wilson Elkins condemning the University's lack of any Black professors, administrators, or even professional staff, and the utter lack of housing for Black students in College Park.

These were pervasive problems in College Park and the University community. Landlords in the city would refuse to take on Black tenants, and the University was extremely reluctant to hire Black employees of any kind. It wouldn't be until 1969, when the Black Student Union partnered with NAACP in an audit of College Park's discriminatory policies, that real change came to pass.

National Programs and increased Black presence

On November 8, 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Higher Education Act. Among other things, the Act established Upward Bound, a program designed for underprivileged high school students to get a jump on college. Students deemed to have "potential," but who had low grades, were invited to live on campus for two weeks, attending classes and social events. At UMD, this ultimately increased the number of Black students enrolled at the University.

Students from two Black high schools were the first beneficiaries of the Upward Bound program at UMD. In July 1966, nearly one hundred students from Baltimore and DC came to experience what UMD had to offer. During their two-week visit, they attended lectures and visited fraternity and sorority houses (which were under fire at the time for their de facto segregation). These students also joined a picket, demonstrating with others who were protesting the University's inaction on housing discrimination in College Park. Even before they were officially enrolled at the University, these high schoolers acted in solidarity with UMD students, recognizing that their agency and activism could make a difference for their futures at the institution.

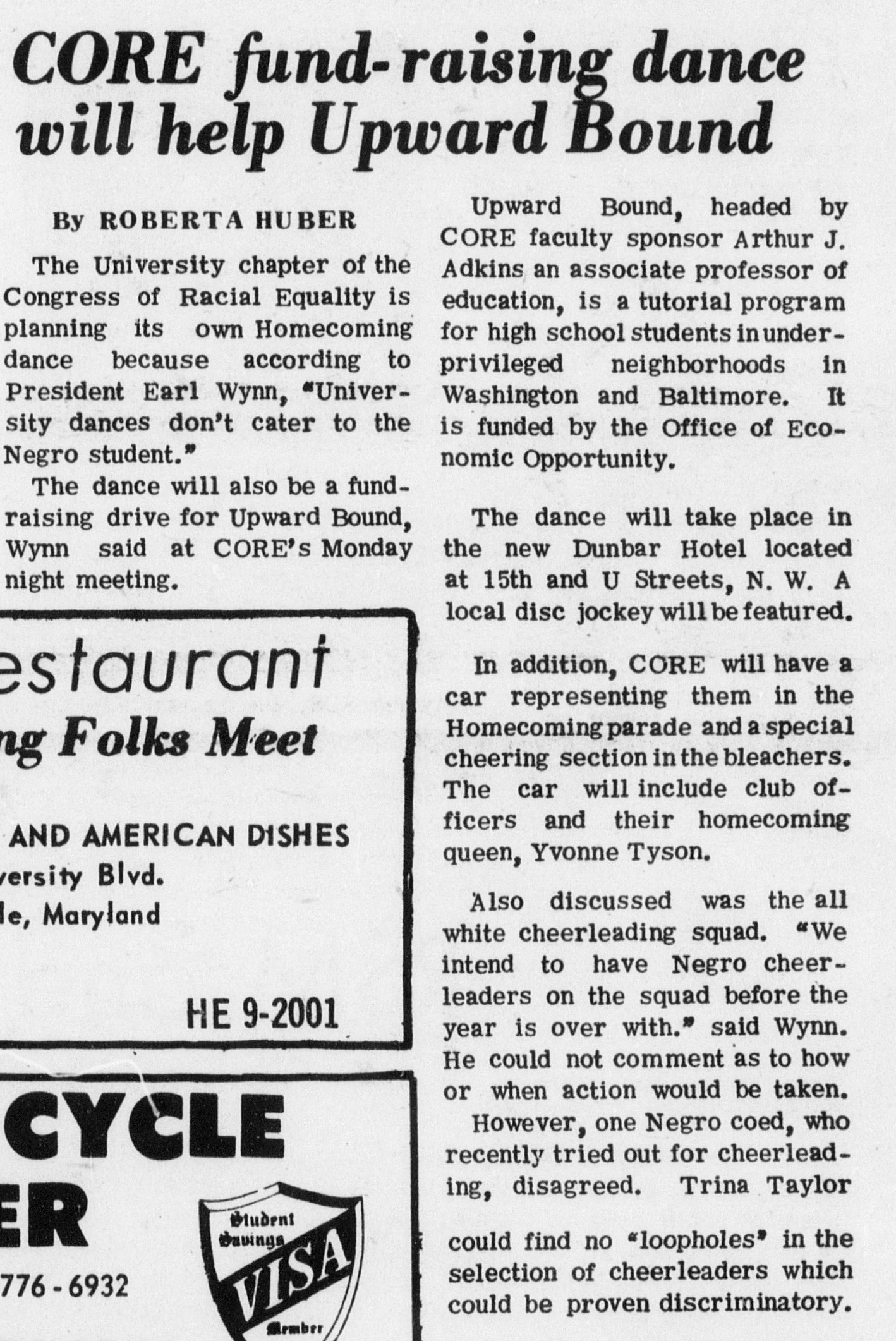

Upward Bound greatly increased the presence of Black students on campus in the late 1960s. Students created a campus chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality in 1966. This chapter was closely aligned with Upward Bound during this time, turning some of their social events into fundraisers for students in the program.  CORE recognized the importance of Upward Bound for the University's Black population, and so invested in support and mentorship for these high school students. The students of CORE recognized that for UMD's Black population to thrive, not only would programs like Upward Bound would have to continue to give Black students a chance, but Black students would have to support one another through the hostile environment that was the University of Maryland in the 1960s.

CORE recognized the importance of Upward Bound for the University's Black population, and so invested in support and mentorship for these high school students. The students of CORE recognized that for UMD's Black population to thrive, not only would programs like Upward Bound would have to continue to give Black students a chance, but Black students would have to support one another through the hostile environment that was the University of Maryland in the 1960s.

By the time of the protest, Black students and community members had been fighting racism from the University for nearly twenty years. This protest was part of a long legacy of Black students having the courage to challenge racist policies head-on, and to demand change from those who told them they didn't matter.